Theatrical Voice Research Centre, University of Surrey, 12-14 June 2025

There was a certain allure and mystery in the air right from the start at this conference on ‘Actors, Singers and Celebrity Cultures across the Centuries’. Katherine Hambridge from Durham University eased us into three stimulating days with a paper on gender and the German voice, delivered entirely – and fittingly – through tinted glasses.

As was only inevitable at a conference on this subject, there was plenty of work presented on divas of all kinds. One idea highlighted by Jamieson Hankins, also from Durham University, was that of the superhuman, metaphysical quality that distinguishes a diva. It’s a characteristic at the very heart of what makes a diva; it’s her – or his, in the case of divos – very essence. The meaning of the word ‘diva’ in the Italian language is ‘goddess’, originating from the Latin word ‘divus’, meaning ‘divine one’ or ‘deified mortal’. Many in the audience seemed to agree that this quality applied to so many of the figures under examination.

One particular prima donna left no doubt as to her huge influence. The wonderfully-titled paper “Luisa Tetrazzini the dissolute”, given by Massimo Ziccari of the Conservatorio della Svizzera Italiana – Lugano, introduced us to the wonders of this remarkable early twentieth-century Italian diva. One of the many highlights was an open-air performance she gave in the streets of the city of San Francisco to a spellbound audience of around 200,000 people. (For perspective, your average opera house has a capacity of around 2,000 spectators.) But perhaps even more memorable, was the way in which he introduced us to the artist. Among the most fabulous cliches about opera singers with big personalities – real or fabricated – this one will be hard to beat. Ziccari opened his paper with a quote from a manager at the Gramophone Company headquarters in Milan: ‘In character she is capricious and wayward, and if you wish to succeed in obtaining her favour you must pamper her like a spoiled child, by sending her gifts, boxes for theatres, paying her compliments and little personal attentions; in a word, you must appeal to the woman in her nature. She is extremely dissolute in her private life and much affected by flattery and champagne.’ Where to even begin?

The (arguably) greatest diva of them all had of course to make an appearance at a conference on this theme. Malo Maleszka from the École Normale Supérieure de Lyon offered us an original take on an aspect of Maria Callas’s life: her correspondence. Malo analysed several of her open letters to the press during the peak of her career (1955-1959). This revealed her artistic personality and her fraught relationship with the press, La Scala in Milan and the Met in New York. One key theme seemed to cut through all her correspondence: her unwavering commitment to her art coupled with her portrayal of herself as a hardworking singer.

Simone Di Crescenzo from Università di Bologna also gave an interesting presentation where he claimed that, on the London stage, the creation of the diva ‘myth’ was inextricably linked to the role of Norma and the singers who interpreted it. Clair Rowden’s (University of Glasgow) paper on divas, their jewellery and the feminine self was a real gem. Here, she explored the many aspects of the relationship between singers and their beloved pieces, encompassing ideas of value, artistic and financial. Her focus was the nineteenth-century star Adelina Patti, the best paid singer of the time, who had her 3,700 diamonds sewn into a ‘spectacular bodice’ that she wore for her final return to Covent Garden as Violetta. The Italian duo Carlo Tortarolo (Conservatorio di Musica ‘F. A. Bonporti’ of Trento) and Rosa Angela Alberga (Independent Scholar) showed us how the Japanese soprano Tamaki Miura leveraged racial biases in her iconic portrayal of Cio-Cio San in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, becoming celebrated in the US and Europe as the quintessential tragic heroine.

It was not all talk at this celebrity-centred conference, however, and we also had two unique performances. Jed Wentz of Universiteit Leiden enlightened us to the wonderful art of declamation, treading the fine line between speech and song that is the essence of the genre. He attempted to re-create the art of Dutch poet and linguist Bernhard Henrik Lulofs (1787-1849) to understand what made his performances so popular and, to do so, he treated us to a declamatorium that was great fun. The second performance, ‘Corset Story’, by Susannah Self (independent composer, conductor, performer and scholar) was a semi-autobiographical one-woman show mixing vocal narrative and singing, accompanied by herself on the ukulele and the piano. She sang about women composers such as Alma Mahler (Gustav’s wife), who was forced to ‘bury her music in the garden’, and also included a touching song in honour of Julia Navalny, widow of the late Russian politician Alexei Navalny.

The conference keynote was delivered by Hilary Poriss of Northeastern University and focused on what she described as the ‘less sexy’ aspects of Pauline Viardot’s career: her work as a vocal pedagogue. She summed it up with Viardot’s own words on the matter: ‘It’s that I find nothing more boring in the world, and I always have something better to do.’ Despite the singer’s lack of enthusiasm for the job, the keynote offered a compelling outline of her teaching trajectory and her relationship with her students. Finally, my own paper addressed the idea of ‘invisible stardom’ as I uncovered the lost Italian opera company of Giuseppe Ramonda, who visited northern Brazil in 1856. Nothing was known about the company; its only surviving remnants – until now – were the paintings of Giuseppe Leone Righini, the company’s scenery painter, today considered by art historians and art auctioneers as ‘the foremost European artist of the nineteenth century to portray the Amazonian landscape’. All the other performers were of a similar calibre.

There were subtle highlights too. Introduced by Emmanuela Wroth of the University of Cambridge, the organisers used Eve Tuck’s feminist approach to facilitating academic questions and answers. This essentially meant that after the papers the audience was encouraged to discuss their thoughts with those around them before asking any questions – which removed much of the stiffness and awkwardness normally associated with the process. This made the experience much more comfortable, and as a result richer and more productive.

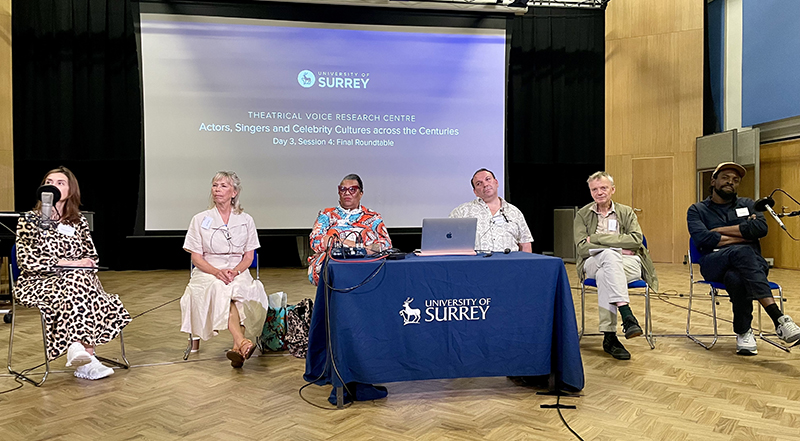

The final day of the conference included an industry roundtable with representatives from major institutions, independent arts organisations and the press: Sally Burgess from English National Opera and the Royal College of Music, Salvatore Scalzo from the Royal Ballet and Opera, Ivan Hewett from The Daily Telegraph, Carol Leeming from Dare to Diva and Tumi Williams from Starving Artists.

The conference was organised by the Theatrical Voice Research Centre, headed by Barbara Gentili of the University of Surrey. It convened academics from the UK, the US and most of Europe, at all levels – from doctoral students to early career researchers and senior scholars. The programme can be found here and the full conference is now available on the centre’s YouTube channel. This was a thought-provoking conference sure to amplify innovation in research in the arts and humanities in future.

Mahima Macchione is a PhD candidate at King’s College London specialising on the Italian opera industry in Milan and its global expansion in the 1830s.