Callum Rogers

Rhené-Baton (1879–1940) was a French musician perhaps best known for his conductorship roles across Europe. Although he was born in neighbouring Normandy, Rhené-Baton gleans much of his compositional inspiration from Breton culture—some of his most important works such as En Bretagne and Au Pardon de Rumengol champion Breton landmarks and culture. His solo-piano publications span thirty-seven years (1901–1938) and total twenty-three opuses (peculiarly, thirty-seven years also separate Debussy’s first and last solo-piano publications: Danse Bohémienne, 1880 and Les Soirs illumines par l’ardeur du charbon, 1917).

It is clear that solo-piano writing was a perpetual interest to Rhené-Baton—even during an eleven-year hiatus of solo-piano composition between 1909 and 1920, the composer reviewed piano technique literature such as Wassili Safonoff’s New Formula for the Piano Teacher and Piano Student, transcribed his own orchestral work for piano, and wrote chanson (French song) for piano and voice. What then, was the reason for this hiatus? I hope to formulate the beginnings of an answer to this question in this blog entry.

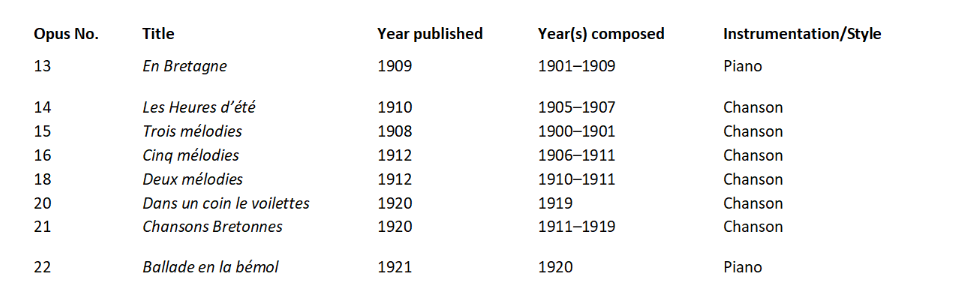

The solo-piano compositions that bookend this hiatus period are En Bretagne Op. 13 (1909) and Ballade en la bémol Op. 22 (written 1920, published 1921). En Bretagne (In Brittany) is a six-piece suite considered to be ‘one of his best works’ (Sordet 1924 ) and is dedicated to pianist André Salomon (1881–1944): a soloist of the Pasdeloup and Lamoureux concerts (where Rhené-Baton would later conduct), pianist in the eighth season of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (where Rhené-Baton would also conduct), and one of the founding teachers of the conservatoire in Troyes. En Bretagne is comprised of six short piano pieces written between 1901 and 1909 with titles that relate to some aspect of Brittany. Ballade en la bémol (Ballad in A♭) is a more substantial piano work of one movement written in 1920, and is dedicated to virtuoso pianist Marie Panthès (1871–1955). In the eleven-year solo-piano hiatus, the composer wrote eight chansons:

The turbulent decade that surrounded the Great War should be reconstructed with a focus on Rhené-Baton’s conducting exploits. By 1908 and when he was 30, Rhené-Baton had published six solo-piano opuses and been entrusted with the conductorship of the choir at the Opera Comique in Paris in 1907, preceding his colleague Albert Wolff who took over the role in 1908. Rhené-Baton ‘reveal[ed]’ himself as a conductor (Malherbe 1910) in the decade that followed, and the period where he relinquished piano composition is best reconstructed as the period that solidified at least publicly, Rhené-Baton the conductor.

Rhené-Baton’s first big break came in 1910 with two concurrent conductorship roles. Firstly, as director of La Société des Concerts Populaires d’Angers (the Angers Popular Concert Society) located just outside Brittany, where he held this position until 1914, and secondly, as director of Le Grand Festival de Musique Française (the Great French Music Festival) at the Munich Exhibition in September. La Société Française des amis de la Musique presented over three nights—and for the first time on German soil—music reserved primarily for ‘the leaders of the young [French] school: Debussy, Dukas and Ravel (Galland 1910) which was to be complemented by older French music by Rameau, Berlioz, Franck, Fauré and Saint-Saëns. During this short festival, there were intimate social gatherings and official receptions, the most glamorous of which was offered to Saint-Saëns by Prince Ferdinand of Bavaria. To be a fly on the wall!

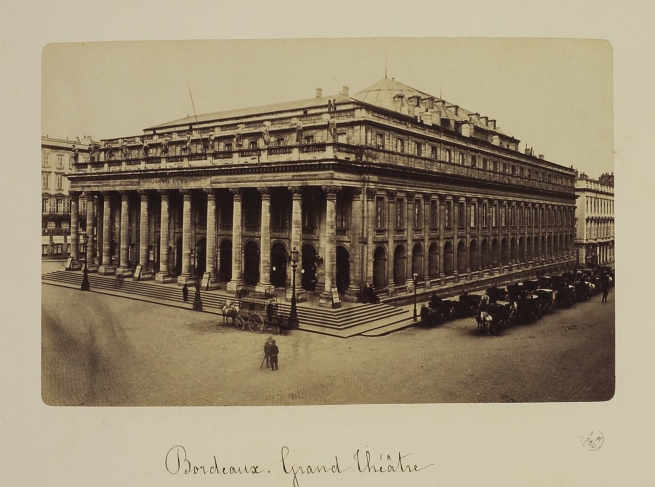

In November and December of 1912, Rhené-Baton conducted two concerts by La Société Sainte Cécile (Saint Cécile Society) to ‘packed’ (Anon 1912) audiences at the stunning Grand Théâtre in Bordeaux. The former programme was an almost exclusively German affair: von Weber’s Overture to Euryanthe, Beethoven’s Fifth, Franck’s Redemption, and Wagner’s Overture to Die Meistersinger. The latter programme was slightly less Germanic: Liszt’s Messe de Gran, Franck’s Panis Angelicus, and Mendelssohn’s Wedding March. Both performances had favourable reviews in the prominent journal La Revue Française de Musique, but questioned the conductor’s supple interpretation of the music:

[November concert] The whole [concert] was conducted with skill by M. Rhené-Baton, who can hardly be reproached except for rounding off the angles a little too much, [and] for sometimes leading with too supple and undulating gestures. A little more dryness would not spoil anything.

[December concert] The additional rehearsals devoted to the development of this [Liszt’s Messe de Gran] difficult and complex work naturally had the consequence that M. Rhené-Baton [wanted] from his orchestra and his singers, well trained by M. Gendreu, [with] even more precision and nuance. The execution was therefore most satisfactory and a complete success. (Anon 1912)

Over-suppleness is a criticism consistent with many contemporary reviews of Rhené-Baton’s orchestral performances. Dominique Sordet writes:

[His] rounded direction, [that is] sensual [and] surrounded gives the impression of a voluptuous [entity] floating on the surface of the sonorous ocean […] Rhené-Baton is not an imperious and abrupt conductor: his interpretations are velvety, supple, broad, more so than precise or rhythmic.

His performances are excellent, although sometimes marred by softness. (Sordet 1924)

The period surrounding the Great War also facilitated a style dépouillé (stripped-back style). In the wake of the catastrophic First World War that claimed almost two million French lives, a fresh start was necessary—a new outlook and restoking of French national identity. In music, this typically embodied a rejection of foreign (typically German) influences which were formerly the cultural currency in France throughout the 19th Century. The conservative French government heralded French Classicism as the vehicle to ‘symbolically reunite a defeated and injured France with its great past’.(Samuel 1918)

Subsequently, composers sought to write music that was stripped of the superfluous; that was concise, melodic, and crucially, French. The term style dépouillé is a genre label used to group and understand 20th Century French music that practiced economy such as Satie, Ravel, Poulenc, and Stravinsky. Some of their music is comparable through their thin textures, pronounced and unobscured melodies, and simplicity. Out with passé virtuosity and in with digestible and economic music.

This might have been a problem for Rhené-Baton—at least from a conducting point-of-view. One might sensibly presume that a velvety, voluptuous orchestral delivery does not align with facets of the fashionable stripped-back style, and that this approach might have been received as an unwelcome hangover from an impressionist (or even possibly, Germanic) yesteryear. I know that if I were a 20th Century composer writing in a stripped-back style, I cannot imagine choosing to premiere a work with a conductor whose velvety suppleness overshadows an ascetic writing style that demands precision and candour. The ‘French Anglophile’ (Hoedemaeker 2013) and editor of The Chesterian Georges Jean-Aubry provided a scathing review of Rhené-Baton conducting Roussel’s Second Symphony, and touches on the prolixity of the interpretation:

The slow and vague tempo he adopted in the last movement unduly lengthened its duration, and perhaps the sensation of prolixity which the last part of the first movement gave us, should be attributed to the same cause. (Jean- Aubrey 1922)

Rhené-Baton worked alongside Monteux, Hasselmans, and Ingelbrecht in conducting the 1912/13 season at Le Theatre des Champs-Élysées, Central Paris, and once that had wrapped up, he stood in for Pierre Monteux as conductor of the Ballets Russes for a performance in July in London and the Ballet’s first transatlantic tour of thirty-two performances in South America. The tour began in Buenos Aires at its relatively young Opera house Teatro Colón on September 11th where they were hosted for one month. The ballet staged Le Pavillon d’Armide (music by Tcherepnin), Le Spectre de la Rose (Berlioz’s Orchestration of von Weber’s Aufforderung zum Tanz) and the ‘Polovtsian Dances’ from the end of act two of Borodin’s opera Prince Igor.

Next stop was Montevideo on October 17th, where the ballet performed twice in a troublesome small venue. They finished their tour in Rio de Janeiro in November. Whilst the South American performances were generally considered a success, the tour is seen to have no intrinsic importance in the history of the organisation as the repertoire contained none of the new ballets of the year, except Florent Schmitt’s La Tragédie de Salomé, which was only given twice (if you haven’t heard this piece already, add it to your listening list… it’s fantastic!).

In 1914, Rhené-Baton was appointed second conductor of the Orchestre Lamoureux for their abroad performances at the Kurzall Theatre of the Grand Hotel Amrâth in Scheveningen, a popular seaside resort of the Hague (which now has a fantastic modern pier). Whilst it is unclear how long Rhené-Baton stood in this role, Henry de Groot suggests that his time at Scheveningen during the war years cultivated the perception of a ‘temperamental’ personality, who always made room for French repertoire in his programming. (Groot 1929)

In 1916, Sordet recalls that Rhené-Baton received a propaganda artistique (artistic propaganda) from the French government during his time in the Hague, and the sympathies he acquired there earned him the directorship of the Dutch Royal Opera for two years. It would be interesting to know what Sordet means by an artistic propaganda, how he learnt of it and the details of such a seemingly lofty task on behalf of the French government.

In 1918, Rhené-Baton was trusted with the revival of the Pasdeloup Orchestra—a conductorship he occupied for most of his professional career until 1932. The orchestra, originally founded in 1861 by Jules Pasdeloup with the name Concerts Populaires, is the oldest orchestra still in existence in Paris. Rhené-Baton conducted the world premieres of some significant works there, such as Aubert’s Habanera (1919), and Ravel’s Alborado del gracioso (1919) and orchestration of le Tombeau de Couperin (1920). This role seemed to occupy most of Rhené-Baton’s time and must have been dear to him (and was likely a good earner), as there is little evidence to suggest he held any notable role alongside this conductorship until at least 1922. As he had done in 1908 with the choir at the Opéra Comique, Albert Wolff took over as the organisation’s principal conductor sixteen years later in 1934. Their professional relationship was longstanding—the RIPM (Répertoire International de la Presse Musicale) database has catalogued an undigitized letter by René Chalupt in The Chesterian (London) that suggests that at least one of the Pasdeloup concerts were co-conducted by the pair in 1928.

Rhené-Baton’s hiatus in solo-piano composition can be explained in part by his drive to establish himself as a conductor—a goal which he undoubtedly achieved. The stability of his role at the Pasdeloup Orchestra afforded the composer the security to begin composing for piano again, and we’re thankful that he did so.

If you have never heard any of Rhené-Baton’s music, I always recommend his Piano Trio Op. 31. You can listen to Trio Hochelaga playing this piece on YouTube here.

Callum Rogers, PhD Candidate, University of Lincoln

Email: Carogers@lincoln.ac.uk

About the author

Callum Rogers is a musicologist and pianist studying for a PhD at the University of Lincoln. He specialises in 19th and 20th Century French Piano music, with a keen interest in philosophy, music analysis, pedagogy, and genre studies. This thesis will dismantle and reconstruct more securely the etymology around style dépouillé alongside the first analysis of composer/conductor Rhené-Baton’s solo-piano catalogue. If anyone is interested in reaching out, please contact CaRogers@lincoln.ac.uk.

Bibliography

[Anon.], ‘Bordeaux—Grands Concerts’ in La Revue Musique de Française (December 15, 1912), pp. 216–7

de Galland, Raoul ‘Saint-Saëns à Alger’ in Revue Musicale de l’Afrique du Nord (November 1 1910), p. 1

Dorf, Samuel N., ‘Erik Satie’s Socrate (1918), Myths of Marsyas, and un style dépouillé’, in Current Musicology, 98 (Columbia University Press: September, 2014), p. 95–119.

Groot, Henry de, ‘Concertberichten’ in De Muziek (October 1, 1929), pp. 35–7.

Hoedemaeker, Liesbeth, ‘The Chesterian’, on Retrospective Index of Music Periodicals 1760–1966, accessible by <https://www.ripm.org/?page=JournalInfo&ABB=CHE>.

Jean-Aubry, Georges ‘Around a symphony’, in The Chesterian, 22 (London: April, 1922)

Malherbe, Charles, ‘Concerts Durand — Exécutions récentes’, in Revue Musicale (April 1, 1910), pp. 189–93.

Raoul de Galland, ‘Saint-Saëns à Alger’ in Revue Musicale de l’Afrique du Nord (November 1 1910), p. 1

Sordet, Dominic, Douze Chefs d’Orchestra (Paris, Fischbacher: 1924)