By Mollie Carlyle

The presence of musical and theatrical events in prisoner-of-war camps has been well-documented both by academics from a wide range of disciplines and also by the men themselves, many of whom kept diaries during their captivity in order to document their experiences and keep track of the passing of time.[i] In a world of confinement, oppression, and forced discipline, music and theatre represented a means of escape for the men and temporary freedom from the lived realities of captivity. Reverend George Chippington, for instance, had been imprisoned in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp and recalls the importance of theatrical events to the morale of the Chungkai hospital camp where he was interned: “They have enabled us, if only for a brief moment, to escape from the harsh realities of this unreal life into that other civilised world from which we came and to which one day we hope to return” (Eldredge: 2014, p. 542 and Chippington, p. 447). Music and theatre served as a connection to the outside world that they remembered and generated a sense of shared hope and purpose for those in captivity. For the interned men, the psychological benefits of these camp entertainments were as much a part of their survival and quality of life as food, water and shelter were. While music and theatre functioned as a means of mental, if not physical, escape from the confined and oppressive world that the men found themselves in, the roles of music and theatre in prisoner-of-war camps were multiplicitous and served several functions within the practical, psychological and social lives of those living in captivity.

Having spoken of prisoner-of-war camps in terms of oppression, constriction and restraint, it may appear oxymoronic to then talk about the shanty, with all its literary connotations of life on the open waves, freedom and nautical adventure. There are undeniable similarities, however, between how we might describe life at sea in a practical sense and the physical conditions of captivity in the prisoner-of-war camps. As a sailor, one is expected to spend months at sea within an incredibly confined context with only your shipmates for company. Granted, there will no doubt be opportunities to explore new places and people when the ship docks in port – the stark shift from restricted shipboard conditions to freedom in port cities around the world no doubt contributing to the somewhat sordid reputation of the sailor. For the most part, however, the sailor spends vast amounts of time in a confined shipboard setting, working in perilous conditions and performing labour-intensive tasks, certainly in the pre-mechanised sailing era. Lack of food was a constant complaint, as were unfair officers and a heavily regimented daily routine. As to where shanties fit into this lifestyle, early collectors of shanties were often quick to emphasise that shanties are not the romantic sea songs that appear in literary depictions of life at sea and are heard sung in a balladic folk style on land. Frank Bullen, who was a sailor from the Age of Sail, wrote that shanties are “songs of labour: the crude symbols of much heavy toil; ofttimes terrible experience and physical suffering” (Bullen and Arnold: 1914, p. xi). Shanties can be defined simply as songs sung as part of maritime work, serving a very real and practical function in the daily lives of the men. Some shanties were used for the entertainment value that the songs could bring to otherwise dull and protracted tasks (such as pumping shanties), particularly aboard the later mechanised sailing ships. The songs were primarily used, however, to carry out laborious tasks aboard ship by keeping the men in time with one another, ensuring that every movement was as efficient as possible. Stan Hugill, who sailed onboard the last of the British commercial sailing ships, states that captains of sailing ships used to compete with one another to hire a sailor with a reputation for being a strong shantyman, as this could literally mean the difference between an easy and an arduous voyage.[ii] Music in a shipboard setting, like music in prisoner-of-war camps, had a multitude of meanings and significance for those singing the songs – at once functioning as an entertainment, a means of escape from the perilous conditions at sea, a social mediator, an expression of identity and personal feeling, and a psychological and physiological tool for carrying out labour-intensive tasks.

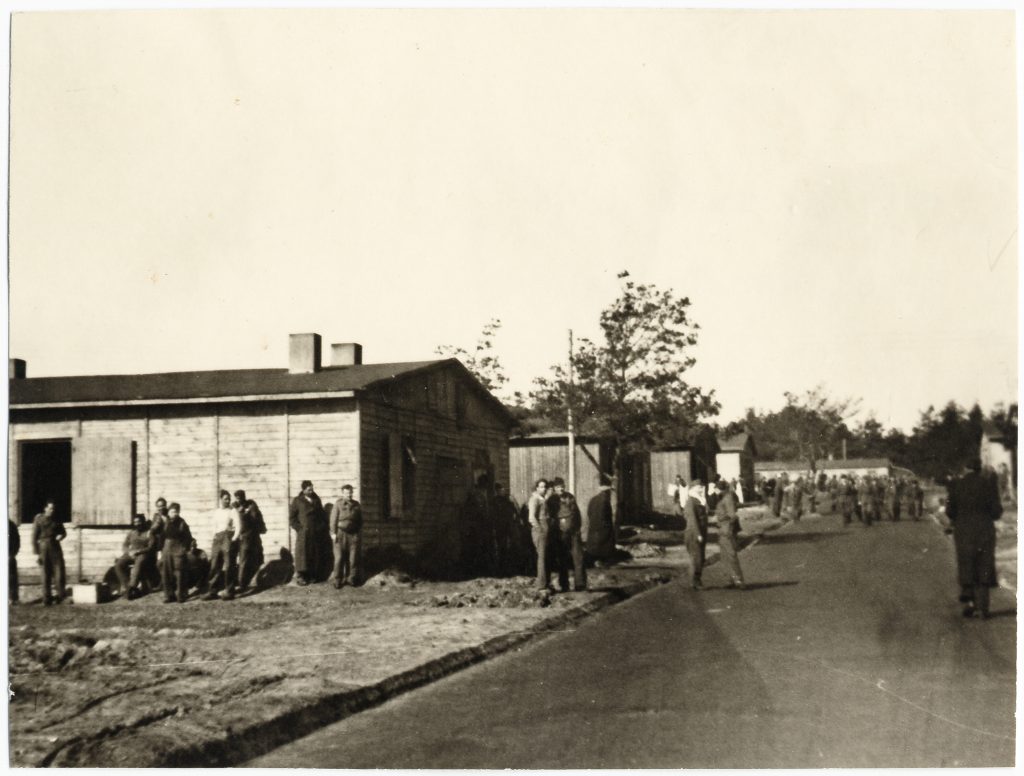

With all of their shared values and functions, it is no wonder that shanties, despite rarely having been sung on land during their heyday, were used to full effect by the merchant seamen interned in prisoner-of-war camps during the Second World War. One camp where we know that shanty singing took place was the Marineinterniertenlager (marine internment camp – commonly shortened to Milag) at Westertimke, Germany, which held merchant seamen prisoners-of-war. Milag Nord counted amongst its number the sailing ship sailor, shantyman and later shanty collector and performer Stan Hugill, who arrived in Milag Nord after his ship was captured in 1940 and remained there until the camp was liberated in 1945. Hugill’s seminal collection of shanties, Shanties from the Seven Seas, features a foreword by fellow sailing ship sailor Alan Villiers, who writes: “My brother Frank was prisoner of war with him in the Marlag-und-Milag Nord. Stan’s cheerful shanteys were a help even there, just as they were in the big four-masted barque Garthpool” (Villiers: 1961, p. ix). When it came to camp entertainments, Hugill appeared to have been a leading figure: writing scripts, designing sets and costumes, and enlivening the men through theatre and song.[iii] Although yet to commit the songs that he knew to paper, Hugill had developed a vast repertoire of shanties from his childhood growing up in a nautical family and from his many years spent at sea in sail and steam. For the merchant seamen in Milag Nord, shanties represented a unifying force that every man, regardless of nationality, would have been at least vaguely familiar with, the genre being so inherently bound in maritime occupations. Shanty singing allowed the men to express their common maritime identity through the summoning up of the old sailing ship songs, symbolising both a nostalgic representation of the seafarers’ lives (often taking a more romantic stance than the lived reality of why and where these songs were used) and their desire to escape captivity to return to the sea.[iv] Just as shanties occupied various functions in their original shipboard work song setting, shanties also had multiple meanings and functions for the men in Milag Nord, who used these songs to fulfill a number of psychological, social and practical needs.

The Marlag und Milag Nord POW camp

First and foremost, shanty singing represented a way in which bonds could form between the interned men of the camp, owing to the innate social and communicative characteristics that shanties possess.[v] In ‘To Keep Going the Spirit’, Sears Eldredge suggests that music “restored the POWs’ capacity for empathy and camaraderie” through shared experiences, communication, and the fostering of a sense of community amongst the men (Eldredge: 2014, p. 546). Eldredge goes on to state that one of the benefits of camp entertainments was that they served the purpose of making men talk by giving them “new topics for conversation, jokes to recall, and music to sing” (Eldredge: 2014, p. 546). Similarly, one of the ways in which the monotony of life at sea was broken up was through the sharing of song – both on deck for work and below deck for recreation. A good shantyman would always be on the lookout for new material to add to their own repertoire and the ship itself acted as a place of musical exchange, where sailors of varied nationality and background would share the songs that they had encountered in port cities and ships around the world. The function of song exchange in both situations is twofold: first, to provide mental and conversational stimuli, and second, to create a reciprocal relationship between those sharing and those learning the repertoire. Within the confined world that the men found themselves in, there was little opportunity for mental stimulation through new experiences, the monotony of life in prisoner-of-war camps often contributing as much to the downward psychological spiral of the men as the cruelties inflicted on them. The sharing of song allowed the men to express their own personal thoughts and perspectives about the music, and gave them a common reference point that every man who was present at the exchange would be familiar with. The song may even become emblematic of their community. Thinking about shanties in particular, even amongst scholars, the repertoire generates much discussion owing to the variety and differing levels of improvisation that the songs were subject to. In a camp of interned seamen, it is more than likely that the sailors would have heard different lyrical versions of the same shanties depending on where they first heard it and which ships they had sailed on. This had the benefit of allowing the men to share personal recollections of a time and place far away from the prisoner-of-war camp (again, relating to escapism) and would also have generated a great deal of discussion about which versions were correct, where they originated and which had the most appealing lyrics. While the men might have disagreed on the latter points, the singing of shanties contributed to a sense of camaraderie through shared experience, both in the exchange of music between the men and also by reinforcing their common nautical background.

Remaining with the lyrical content of the shanties, another characteristic of shanty repertoire that had particular relevance for the men in Milag Nord is the humour that is present in the lyrics. The humourous content of the shanties not only allowed for further discussions of different versions of shanties (for instance, comparing bawdy versions of shanties that they knew) and provided light-hearted relief from the hardships of life in the camp, but also functioned as a form of resistance against oppressive forces – both physical and psychological. One of the ways in which the lyrics of shanties were adapted at sea to fit the specific circumstances that the shantyman found himself in was through the use of humour to poke fun at those in positions of authority on the ship. While the crew risked punishment if certain sentiments were spoken, there was a certain amount of leeway when it came to expressing these same sentiments through song, as the shantyman could quickly inform the captain, cook or officers that the words were just part of the shanty or referred to a different crew on a different ship. The well-known shanty, ‘Leave Her, Johnny, Leave Her’, for example, was often sung at the end of a voyage and gave the crew the opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with their fellow crewmates, officers, food, and the voyage in general.[vi] Adapting the lyrics of shanties in response to oppression was not limited to a maritime context, however, as Stanton H. King, the official shantyman of the US Navy, demonstrated by publishing a book of shanties with lyrics that reflect the wartime context of the book’s release. King’s collection features shanties such as ‘Roll the Kaiser Down’, with its rallying lyrics:

We have heard our President and leader say,

“Go roll the Kaiser down!”

We have heard our President, our old friend, say,

“Go roll the Kaiser down!”

Go roll him down and batter his crown,

Go roll the Kaiser down!

Go roll the German Kaiser down,

Go roll the Kaiser down! (King: 1918, p. 9).

In ‘Humor as a coping mechanism: Lessons from POWs’, Linda Henman discusses the importance of humour in encouraging resilience and survival amongst repatriated Vietnam POWs, arguing that “the creation of humor is a well-defined system of social support” (Henman: 2001, p. 83). By adapting the lyrics of shanties to reflect the specific conditions and context of Milag Nord, the interned men were able to fight back against the material reality of their captivity (the facilities, the officers and the routines that they were subject to) and also to keep the resilient spirit alive as a community through inside jokes and humour. Reverend George Chippington also alludes to this intangible form of rebellion in prisoner-of-war camps through music and theatre, noting his impassioned response to the rumours of the destruction of the Chungkai camp’s theatre in his wartime diary:

The order to demolish the theatre is yet another humiliating admission of defeat on the part of the Japanese. They cannot destroy the spirit which created and gave rise to our theatre – so, their answer, destroy the fabric, the bits and pieces of the theatre – the inanimate expression of that spirit they have failed to conquer (Eldredge: 2014, p. 542 and Chippington, p. 447).

Chippington states that while the material object of the theatre itself – its parts, its fabrics, its props – can be destroyed, the theatre represents more than just a physical place where performances are held and is instead a direct reflection of the ‘unconquerable spirit’ of the men. For the interned seamen of Milag Nord, the singing of shanties – a distinctive genre of song born of and belonging to the sea – was a clear expression of identity and resilience, making the statement that although the men have been taken away from their livelihood and occupation, their spirit remains resilient through singing the humourous, memorable, and lively songs that they share with one another.

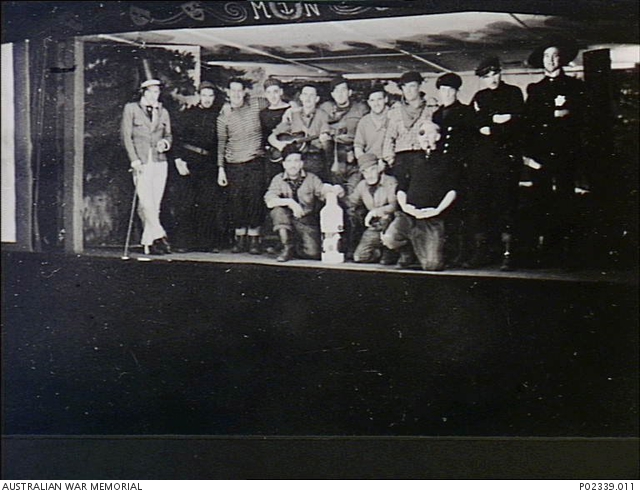

Interred seamen performing Stan Hugill’s Barbary Coast 1849

There is no doubt that shanties fulfilled a number of psychological needs for the interned men of Milag Nord during their captivity, providing relief from the horrors of the camp, creating social bonds and a community spirit amongst the men, and representing an intangible form of resistance against those who wished to suppress the men’s identity and resolve. Music and choice of repertoire are useful indicators of the emotional states of the men engaged in music-making and reception, and have the added benefit of allowing those involved to express themselves emotionally in a manner that is non-violent (therefore not likely to incur punishment) and psychologically sustainable. Kelsey McGinnis’ thesis, which explores the meaning and impact behind musical productions amongst German prisoners-of-war at Camp Algona, Iowa, writes of the choice of repertoire performed by the prisoners-of-war: “musical programs seem to have facilitated the expression of a wide variety of emotions and sentiments: deep and persistent homesickness, hopefulness, valor, and mourning” (McGinnis: 2015, p. 14). To those in captivity, music has been described as “food of the spirit” and the choice of song, its personal meaning and content, helped to nurture and sustain the psychological wellbeing of the men (Durnford: 1958, p. 144). Humour was certainly one element of why shanties were sung amongst prisoners-of-war in Milag Nord, there being no shortage of humourously bawdy songs and opportunities to improvise new lyrics to fit the specific circumstances of the men. There is also, however, something strikingly familiar and relatable in the sentiments expressed in shanty repertoire when it came to expressing the desires of the men singing the songs. On the one hand, we have the base desires that one expects of a group of men who have spent months at sea with only each other for company: loose women, good food and plenty of alcohol. On the other, despite the fact that shanties were rarely sentimental, shanty lyrics often speak of the sailors’ desire to return home to the world they left behind and their hopes for a better life.[vii] Life at sea, especially in the sailing ship era, was fraught with danger and the men in the merchant service received low wages in return for backbreaking work and the risk of death. The shanty lyrics, therefore, would have had a certain level of resonance with the captive men of Milag Nord, who could empathise with the sentiments of the sailors (both as sailors themselves and as prisoners) and transpose their own personal meaning onto the lyrics of the songs as a means of self-expression. Music was used for evoking and regulating both emotion and memory, as despite the circumstances that the men found themselves in, repatriated prisoners-of-war would often look back fondly on the songs, jokes, and stories that were shared during their time in captivity. George Diamond, for instance, was a prisoner-of-war in a German camp who conveyed a mixture of humour, positivity, and camaraderie in his account of captivity:

Most of my Stalag mates have related the grimness of our imprisonment and have given the American people a chance to [w]onder over the horrors of the loss of precious freedom. But very few have told of the pleasant thoughts and activities. For me, the axiom about unpleasant happenings being forgotten while pleasant ones remain has been the rule, and as I turn the pages of my little diary I always get a big kick out of recalling some of the songs we used to sing in our spare time (which was a full twenty-four hours a day) (Diamond: 1949, p. 177).

Scott Church, looking at the coping strategies of American prisoners-of-war, suggests that this regulation of memory is a form of coping mechanism against the horrors that the individual experiences and, to this end, “may help an individual maintain a sense of control during a crisis” (Church: 2017, p. 165). Again, we can find in this a psychological resilience against oppression and the conditions of captivity, where the mind prioritises the moments of individuality, resistance, and expression of self in the memory’s autobiography of the time spent in the prisoner-of-war camp. For George Diamond and Frank Villiers, autobiographical regulation induces them to look back fondly at the music that they used to sing, which for them signified camaraderie, humour (in the face of oppression), and both the community and personal spirit that were part of their continued survival in the camp.

To the interned men in the prisoner-of-war camps during the Second World War, music was an indispensable part of their daily lives and was used to full effect to boost morale, reinforce community and camaraderie, and provide temporary escapism. While a range of styles and genres could be heard sung or played by the prisoners-of-war, shanties lent themselves extremely well to the circumstances that the men found themselves in. A number of parallels can be drawn between how, where, and when shanties were sung in their original shipboard work setting and the physical and psychological realities of life in a prisoner-of-war camp. As a social tool, shanties were used to invoke a sense of camaraderie and community, create shared experiences through the reciprocal relationship of song exchange, and provide conversational and mental stimuli in the monotony of a regimented lifestyle. Shanty singing in prisoner-of-war camps can also be seen as a symbol of rebellion and defiance in response to oppression as the often humourous content of the shanty’s lyrics was used to belittle the authority of the camp’s officers and make light of the conditions of their captivity. Furthermore, as such a distinct genre of maritime song, shanties were emblematic of the occupation of the merchant seamen at Milag Nord and thus acted as a statement of identity within the oppressive regime that sought to reduce the men to simply a set of numbers. The singing and sharing of shanty repertoire were consequently seen by those involved as a positive aspect of life in captivity and remembered fondly after the fact even amidst the atrocities that the men had been witness to. This self-regulation of memory as a coping mechanism can help to explain why theatre and music have been so well documented in accounts of this era in history; however, it is intended that this article will help to draw attention to the hitherto unexplored aspect of musical life in the Milag Nord prisoner-of-war camp. Shanties found themselves unusually well-suited to the task of providing for the social, psychological, and practical needs of the interned men, owing to the uniquely paralleled circumstances of the genre’s creation and development. The study of shanty singing in prisoner-of-war camps contributes to our understanding of survival strategies in captivity and also allows us to explore a moment in the shanty’s history that has received little attention.

[i] In Captive Audiences/Captive Performers, Sears Eldredge discusses the importance of artistic endeavours (often related to theatrical productions), which “served as material witness to living memory” (Eldredge: 2014, p 543). By creating something physical such as artwork or by keeping a diary, the prisoners of war were creating tangible testimony to their experiences, ensuring that they would not be forgotten.

[ii] Stan Hugill states that “Captains used to fight each other to get a good singer aboard the ship because it made the work go well. If the song went well, the men went well”(Hugill: 1987).

[iii] Like many of the interned men, Hugill kept diaries during his captivity, including a beautifully detailed scrapbook of set and costume designs from the theatrical productions that he was involved in.

[iv] The last of the British commercial sailing ships was wrecked in the 1920s and the age of the merchant sailing ship was more or less over by the end of the nineteenth century. Hence, Hugill was quite unusual for having spent such a large percentage of his maritime career in sail. As such, there would have been an imagined element to the shanty singing that occurred in the prisoner-of-war camps, where shanties were depicted as nostalgic symbols of a way of seafaring life that no longer existed, conjuring up nationalistic elements of ‘Britannia Rule the Waves’ – of British defiance in the face of opposition, and a literary romanticism of the life of the old sailing ship sailor.

[v] Ethnomusicologist Gibb Schreffler’s definition views the call-and-response between a shantyman and the crew as one of the defining features of the shanty (Schreffler: 2018). Shanties are social by definition as one cannot have a shanty without a chorus. Like Stan Hugill used to say, ‘a shanty without a chorus is like eggs without salt’.

[vi] “Now, the times are hard and the wages low…”, “Now, the captain don’t like to give us our pay…” (Doerflinger: 1972, pp. 89-90); “The work wuz hard an’ the voyage was long, The sea wuz high an’ the gales wuz strong…”, “The grub wuz bad an’ the wages low…”, “Oh, our Old Man he don’t set no sail, We’d be better off in a nice clean gaol…”, “The mate wuz a bucko an’ the Old Man a Turk, The Bosun wuz a beggar with the middle name o’ Work…” (Hugill: 1961, pp. 218-19); “She shipped it green and she made us curse, – The mate is a devil and the old man worse…”, “The winds were foul, the trip was long…”, “I’m getting thin and growing sad, Since I first joined this wooden-clad…” (Colcord: 1921), pp. 58-9).

[vii] Outward and Homeward Bound: “An’ when our three years they are out, ‘Tis jolly near time we went about, ‘An when we’re home an’ once more free, Oh, won’t we have a jolly spree” (Hugill: 1961, p. 387); Sebastopol: “The Crimean war is over now, Sebastopol is taken […] So sing cheer, boys, cheer, Sebastopol is taken; And sing cheer, boys, cheer, Old England gained the day (Masefield: 1906, p. 364); Shenandoah: “Oh, Shenandoah’s my native valley, Away you rolling river! […] Shenandoah, I long to see you, Away we’re bound to go, cross th’ wide Missouri!” (Bone: 1931, pp. 104-5); Early in the Morning: “Now my boys to home we’re near, The Lizard Light is burning clear […] So early in the morning. Now my boys we’re at Gravesend, We’re nearly at our journey’s end” (Pease Harlow: 1962, p. 107).

Bibliography

Bone, Captain David, Capstan Bars, (Edinburgh: The Porpoise Press, 1931).

Bullen, Frank and Arnold, W. F., Songs of Sea Labour, (London: Swan & Co., 1914).

Chippington, George E., ‘Diary’, Imperial War Museum PP/MCR/298 [microfilm].

Church, Scott, ‘“I Lived Because I Was Blessed”: Coping Strategies of American Prisoners of War’, Ohio Communication Journal, 55, (2017), 165-178.

Colcord, Joanna, Roll and Go: Songs of American Sailormen, (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1921).

Diamond, George Arthur, ‘Prisoner of War’, New York Folklore Quarterly, 5, no. 1 (1949), 177.

Doerflinger, William Main, Songs of the Sailor and Lumberman, 2nd edition (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1972).

Durnford, John, Branch Line to Burma, (London: Macdonald, 1958).

Eldredge, Sears, ‘“To Keep Going the Spirit”: What Music and Theatre Meant to the POWs’, Captive Audiences/Captive Performers, (Macalester College, 2014).

Henman, Linda D., ‘Humor as a coping mechanism: Lessons from POWs’, HUMOR, 14, no. 1 (2001), 83-94.

Hugill, Stan, The 1987 Liverpool Maritime Festival, dir. Terry Wheeler, (BBC Northwest, 1987) [DVD].

Hugill, Stan, Shanties from the Seven Seas, (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1961).

King, Stanton H., King’s Book of Chanties, (Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1918).

Masefield, John, A Sailor’s Garland, (London: Methuen & Co., 1906).

McGinnis, Kelsey Kramer, “The Purest Pieces of Home”: German POWs Making German Music in Iowa, Masters Thesis: University of Iowa (2015).

Pease Harlow, Frederick, Chanteying Aboard American Ships, (Barre Publishing Company, 1962).

Schreffler, Gibb, Boxing the Compass: A Century and a Half of Discourse About Sailors’ Chanties, (Loomis House Press, 2018).

Villiers, Allan, ‘Foreword’, Shanties from the Seven Seas, ed. Stan Hugill, (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1961).

MOLLIE CARLYLE (molljcarlyle@hotmail.co.uk) is a maritime music scholar currently conducting research into the sea as a place of musical exchange and the movement of maritime song repertoire from a global perspective. Mollie recently completed her doctorate on ‘The Life and Legacy of Stan Hugill’, the last shantyman, which was a joint project between the Department of Music and the Elphinstone Institute for the study of Ethnology, Folklore and Ethnomusicology at the University of Aberdeen.