“Elegie Pal Fischiosauro”: an Experiment in Cryptid Sonic Ethnography

By Luigi Monteanni

“Reality is normally far more mysterious and captivating than any trite expectations you happen to write into your script. It continually serves as a bitter reminder that however long and hard your work on said script, it often isn’t worth the paper is printed on.”

Soda Kazuhiro, Why I Make Documentaries: on Observational Filmmaking

“Avevamo studiato per l’aldilà

un fischio, un segno di riconoscimento.

Mi provo a modularlo nella speranza

che tutti siamo già morti senza saperlo.”

Eugenio Montale

In this post, I am going to analyse the process leading me and my music project Babau to realise a sound art piece transducing a folkloric tale into music, and specifically the genre of the radio drama or children’s audio stories. By composing a work of sound art retelling the story of a specific sonic cryptid named the Fischiosauro (literally, whistlesaurus), I argue that we can illuminate new ways to produce works that aurally investigate the preternatural – something beyond the normal or usual but not beyond the physical laws of nature and therefore linked to hidden, or stranger dimensions of reality. Theoretically, such approaches expand on the concepts of research as composition and field recordings of the monstrous emerging in the research of, respectively, scholars Steven Feld and Mark Peter Wright.

In April 2025, my musical project Babau won the Casamia artistic residency in Cleulis di Paluzza, Friuli (Italy). Casamia is a residency for musicians bringing life to the mountains and taking place in different locations of Carnia. Carnia is a quite isolated historical-geographic region in the northeastern Italian area of Friuli, located south of the main Carnic Alps chain, in the northwest of the Udine province; it is bounded to the north by Austria and to the west by the Italian Veneto region. Historically, this mountainous borderland has been inhabited by peasants and shepherds, and hosts small, underpopulated municipalities which, excluding Tolmezzo and its population of ten thousand, range from a maximum of around two thousand to a minimum of slightly above two hundred inhabitants.

Babau is formed by the author and artist Matteo Pennesi. For the last ten years, with a number of releases on imprints like Discrepant, Bamboo Shows and our own label Artetetra, we have explored possible intersections of fourth world,[1] computer music, and transglobal sonic subcultures in the post-internet age.[2] With albums and sound installations building on uses and misuses of digital folklore and music theory, our work has been defined as an ongoing investigation into sound as a vessel for digital myth-making[3].

Recent releases by Babau.

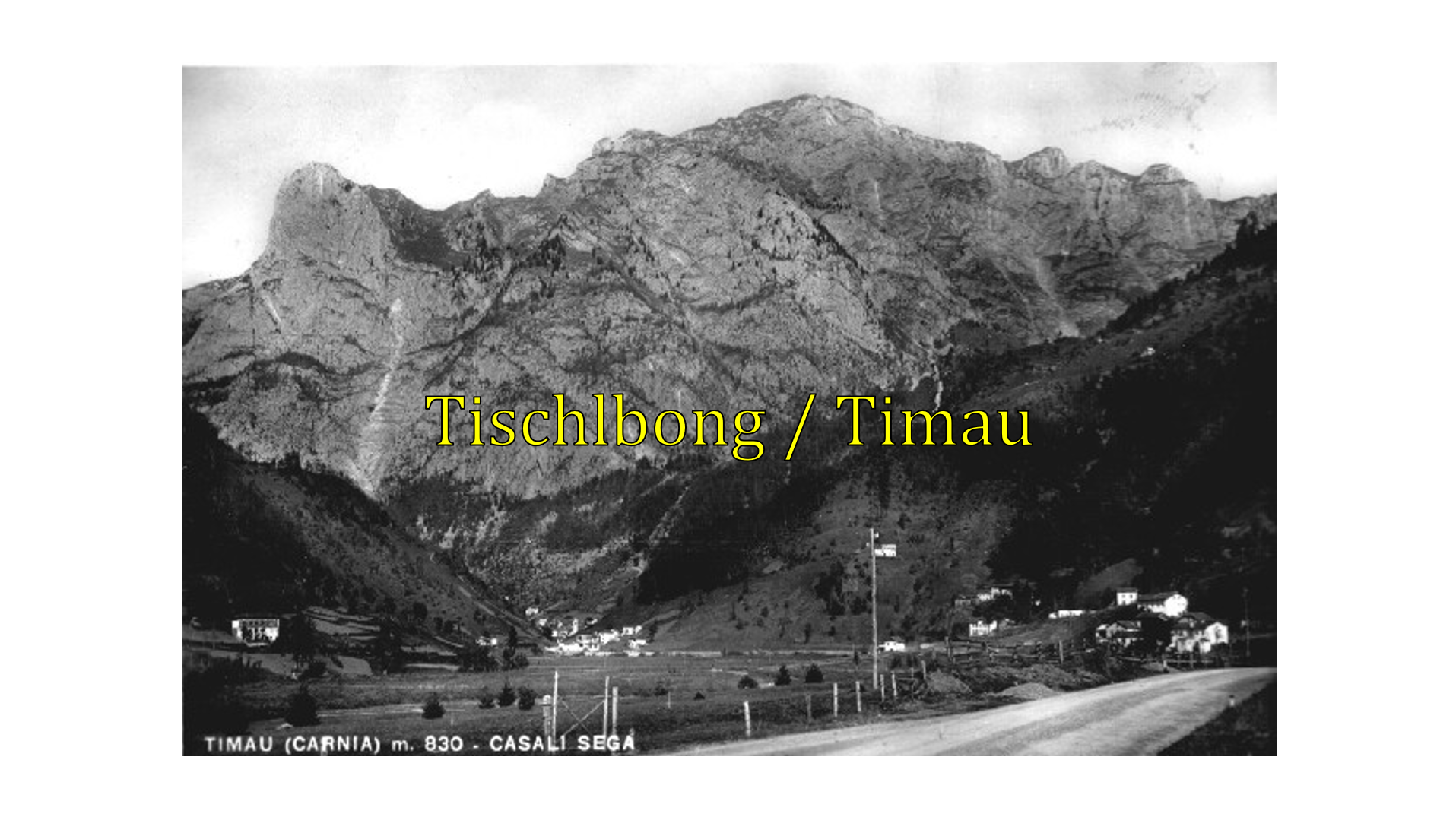

When we received the residency invitation, we began researching information, stories, facts and legends about Carnia. Through internet probing, we found the Fischiosauro story, a reptilian cryptid – a creature like the Loch Ness monster or Big Foot that has been claimed, but never proven, to exist – living in the Leitn swamp, in the 350-people hamlet of Timau/Tischlbong, one of the five fractions of the Paluzza municipality; the only place where the Timavese or Tischlbongerisch – a Southern Bavarian language developed in a Carinthian form – is spoken.

Paluzza’s location on Google Maps and a representation of the Carnic carriers, working women peasants from the area.

As the story goes, around the mid-50s, at dusk, Paluzza’s inhabitants began to hear a high-pitched, piercing whistle reverberating in the air and reaching their homes. Due to unclear circumstances, Timau’s and Paluzza’s inhabitants attributed this sound to an unidentified animal. The population decided that it must have been a water snake. In a book documenting the story, which I’ll examine in a minute (Screm 2023), we found proof of people believing the Fischiosauro’s existence, since some locals would go down the swamp to pour bleach in the waters, hoping to preemptively kill the creature.

When we arrived, we realised that thanks to a fortuitous coincidence, our residency flat was literally above the swamp. Starting to gather the story’s shards and fragments from locals, we learned that part of the story was fabricated. According to a volume published by the academic Udine editor Nota, Pakai: il Trio che si è Fatto in Quattro(Screm 2023), which was donated to us by the Casamia residencies team upon discovering our interest in the Fischiosauro, a local polka trio named Pakai hijacked the story, adding to it and making it grow in time. Part prank, part experiment, not only did these musicians try to convince Paluzza’s inhabitants that the creature was real, but they also staged the Fischiosauro’s defeat by bringing a small snake to the swamp beforehand and then faking a fight, which was documented by a local illustrator (Screm 2023).

In blue, the Pakai trio.

Watch Trio Pakai perform the song “Il Fischiosauro.”

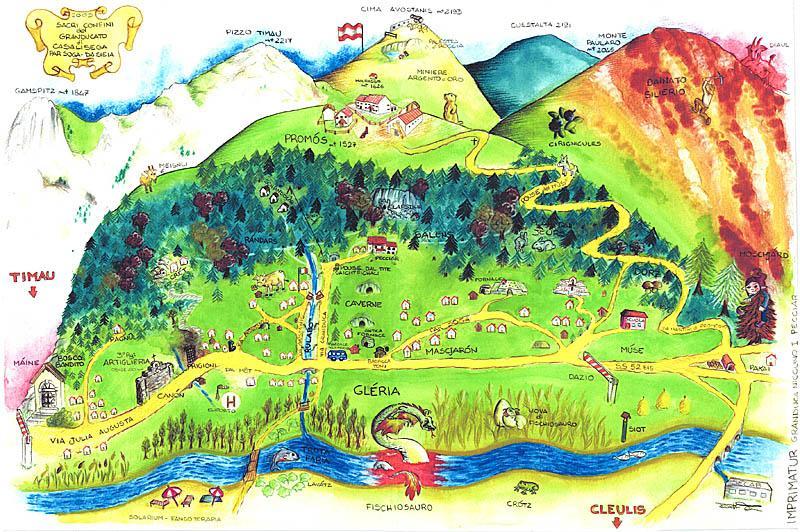

It is also partly speculated that these musicians may have actually produced sounds in the marshes to ensure the noises’ continuity. Following these happenings, interest in the Fischiosauro became a niche of national and international interest. A dedicated bar (Bar al Fischiosauro) was founded, and for almost a decade, until the mid-60s, tourists visited the Leitn marsh by bus, hoping to spot the legendary animal. Today, the creature survives in the celebrations of the Grand Duchy of Casali Sega, a parody, fictional separatist country extending over the territory in front of the swamp, structured around the Fischiosauro myth, and as a children’s story through which they are taught to fear and respect the marshes and their inhabitants (1999).

An illustration of the Fischiosauro from the national paper La Domenica del Corriere and an international coach bringing tourists from Austria to Paluzza to visit the swamp.

Map of the Grand Duchy of Casali Sega.

Overall, it was interesting to notice the layering of different aspects of sound emerging from this anecdote. First, we were exploring a sonic event related to preternatural listening: something out of the ordinary, but not supernatural. Secondly, these sounds are obviously related to memory and language, as everybody recalls the Fischiosauro’s story, especially in the Timavese language, but no one could reproduce or actually describe its sound, as many, if not all, of the original listeners are now dead and at the time, no recording equipment was available in the territory to record the Fischiosauro. Third, the sound was also linked to imagination and musical practice on a literal level as the Pakai polka trio shaped the story by participating as musicians and local personalities. Last, but not least, the swamp was a silent but present sonic source. As an external frame to these elements, let’s also mention the type of imagination inside which the Fischiosauro existed: a universe of medieval-influenced grand duchies and children’s folk tales, which retroactively had given an aesthetic home to what remained of the cryptid.

Since our aim was composing these different layers into a composition, I cannot stop thinking about how such processes echo Steven Feld’s concept of research as re/composition. Feld conceives that “recomposing is a way of imagining across boundaries, whether they are the received boundaries of society and nature, or of music and sound, or of heat and danger” (2025: 133). Drawing from anthropologist Philippe Descola, Feld appropriates the idea of recomposition to address the epistemological violence of reified categories of the natural and social world by changing the focal point. Such an endeavour is pursued, for instance, by “recomposing the relationship between birds and humans by listening to and producing a soundtrack where they are equally present” (2025: 141). In this sense, research as re/composition reassesses boundaries dialogically through care, concern, obligation and responsibility. It provides an answer to Feld’s question: “how do we circulate something in the world and understand this circulation as an ethical response to the conditions of the world and the need to be engaged with those conditions?” (2025: 135)

Yet, although the idea of a recomposition of boundaries and dowels sounds about right for such an ethno-sonic research, the Fischiosauro’s situation was much different than the ones of Bosnavi birds or Ghanaian jazzists studied by Feld. For once, this story missed several pieces (e.g. what did the Fischiosauro sound like?). Additionally, these voids were complicated by processes of invention and fabrication (Pakai trio’s interventions), resulting in long and complex layerings of a cryptid telephone game. How to re/compose a puzzle full of holes?

Since much of this universe was taking place in a legend, defined by Friulian historian Giovanni Panzera as “the border between reality and imagination,”[4] we had to find a new way to access the feeling of a hidden and strange nature; a work that, similarly to the nature of the Fischiosauro, would reveal and explain as much as it would conceal and hide. This feeling of opacity and ambiguity was key to the story. Hence, we wanted to realise something that would superimpose and make somewhat interchangeable all the story’s aspects in a way for which they would become metonymical of one another; in which musicians, imaginary beings, animals, memories and landscapes would come forward as a network of intertwined, mutually implied knots. To obtain such an effect, since cryptid sound studies research and art practice is scarce, we relied on ways we could use field recording and audio manipulation as conceptual, narrative tools, resonating with practice-oriented theorisations of preternatural listening/sounding.

Preternatural listening is a sonic experience beyond the normal or usual, but not beyond the physical laws of nature. Therefore, preternatural listening underlines the sensory attention for hidden, or stranger dimensions of reality, often mixed with an interest in unveiling such dimensions through acts of (and/or audio technologies for enhanced) listening. Examples of preternatural forms of listening are the ones connected to cryptids. Since the invention of recording devices, in fact, as music historian Francesca Brittan reminds us, one of the main interests was to use recording as a scientific tool to reveal the existence of similar creatures, such as fairies, to prove the all-sensing power of technology (2011). Then, preternatural listening documents a tension between the natural and the anomalous.

The link between the super/preternatural and the ecological is not new. Anthropologist Niels Bubandt has underlined how, as natural conditions become more unfamiliar and extreme due to phenomena like climate change, the more their uncanniness takes the form of something beyond nature’s realm (2021). Such an argument hints at the importance of looking at nature and its monstrous aspects through the lens of post-human imagination and the evolutions of folklore, confirming the relevance of narrating the Fischiosauro from this perspective. Indeed, as the renowned Wikipedia list of unexplained sounds shows (e.g. the upsweep, the hum), uncommon aural phenomena and speculations regarding their preternaturalism are linked. Many of these sounds, which have been originally attributed to unseen creatures, proved recently to be caused by undiscovered natural occurrences and anthropic events.

Such a relationship between nature and its spooky doubles also emerges from the Fischiosauro’s afterlife. As confirmed by locals during conversations, today, one of the (fictional) but preferred explanations for the disappearance of the Fischiosauro is that possibly this singular animal needed a specific environment. Now that the swamp is facing its demise due to anthropogenic causes, such conditions allowing the Fischiosauro to thrive are compromised. Conversely, locals noticed how such a happening is confirmed by the appearance of new words in the Timavese/Friulan vocabulary, indicating animals that didn’t live in the swamp, namely ducks and herons (anatras, airons).

The link between field recordings, nature and sound art has been explored in depth by scholar Mark Peter Wright, who, besides having worked at the intersection between cryptids and sound art, in his Listening After Nature (2023), analyses the relationships between field recordings and the monstrous, a trait embodied by cryptids. According to Wright, the monstrous operates outside of the assumed natural order of things, blurring bodies, landscapes, and categories as a result. Ghosts and monsters are distinct but inextricably linked in these discussions. Monsters, in contrast to the individual conceit, emphasise symbiosis, the enfolding of bodies in evolution and in every ecological niche. Monsters emerge as uncertain cultural beings containing an intriguing simultaneity or doubleness. As literature researcher Jeffrey Cohen writes in a quote from Wright’s book:

The monster commands, “Remember me”: restore my fragmented body, piece me back together, allow the past its eternal return. The monster haunts; it does not simply bring past and present together, but destroys the boundary that demanded their twinned foreclosure […] Monstrosity, we must remember, is never exclusively human or nonhuman, more a crosshatch of both. (1996: ix-x)

When transposed to sound, relationships between the natural and its shadows show that preternatural modes of listening chart the gaps between our normative listening habits and the distancing of the natural from its supposed behaviour. Therefore, preternatural listening also entails a continuous normalisation of such sensory uncanniness and ambiguity: getting used to stranger and more monstrous aural experiences; metonymies of new, unexpected forms of nature.

To bring to life these theories alongside the Fischiosauro, we realised a 27-minute sonic elegy and cryptid ethnography incorporating aspects and stylistic elements stemming out of practices of ethnographic documentation, musical composition, sound improvisation and accidental recording. We operated inside the stylistic boundaries of genres such as radio drama and children’s audio stories, formats dear to Timau’s demographics: the elders of the Granducato Casali Sega, for whom the radio was a privileged means of audition and connection, and children who would listen to the story in the form of a fairytale. The “elegiac” feeling, reflected in the title, mirrors the ambiguities of the anxieties linked to the Fischiosauro: the instinct that brings the Timau inhabitants to interrogate themselves on why the creature has disappeared; an anxiety evoking environmental concern as much as the feeling that the Fischiosauro’s haunting speaks of something unresolved.

First of all, following the example of works by sound artists such as Christopher DeLaurenti and his To The Cooling Tower, Satsop, where he recorded himself performing in space, we co-composed the soundscape alongside the Leitn Swamp. Against conveying a traditional, naturalistic perception of the swamp, we instead brought our acoustic and digital instruments – aerophones and an iPad performing into a Bluetooth speaker hanging from trees – to the marshes and recorded ourselves improvising in/with the landscape in order to document a series of different and uncertain timbrical speculations on the Fischiosauro’s whistle. This first and fundamental phase allowed us to explore the landscape using sound as a dowsing tool, at once blatantly showing our unerasable presence in the marshes and hiding our identities behind sounds whose source remains uncertain; it would be difficult to determine through simple listening what instruments (or apps) exactly we are playing and how. Additionally, such recordings were lately manipulated in order to push audio into a zone where listening experiences of those audios would convey a sense of familiarity (the sounds of some kind of natural environment) as much as of weirdness; the uncanny valley of listening.

The result is somehow an open-ended, layered experience. Given the density of characters, meanings and sonic experiences embedded in the Fischiosauro story, our swamp improvisations could be equally read as us making an impression of the Fischiosauro, us trying to conjure the animal through DIY, experimental equivalents of bird whistles, and us recreating the event of the Pakai trio hijacking the sound with their own prankster executions. This logic also incorporates a practical reflection on the origins of sound recording, which, since Ludwig Koch’s Common Shama documentation in 1889, has evolved thanks to a logic of capture akin to the one of the colonial explorer, military strategist or wildlife hunter (Wright 2023). Since the swamp is today a heavily anthropogenic space, a “faithful” sonic representation also meant letting the sound of cars and woodchippers infiltrate field recordings and letting these elements influence our improvisational practice by experimenting with the resonances and sonic textures of industrial waste left around in the landscape, stimulating those by playing music into them and providing sound with a texture and body on the fence between the human and non-human.

Different steps of the recording process. Ph. by Denis Blarasin.

To this phase, which constituted the body of the work, we added an intro and outro, bringing together influences from local music traditions and the opening/closing skits of radio dramas and audio stories. Lastly, we asked Velia Plozner, a teacher who now lives where the Bar al Fischiosauro used to be, and who was alive at the time of the happenings, to provide an improvised voiceover retelling the story of the Fischiosauro with a tone and words apt for the chosen genres. Yet, we were not happy with the possibility of a narrative voice giving away all of the Fischiosauro’s magic and mystery. As a solution, we asked Velia to tell the story in Timavese. This decision not only conformed to the local ways of actually telling and discussing this tale, but made also impossible for non-Timavese listeners to understand the story, thus providing another element which, albeit familiar – knowing the story of the Fischiosauro, the listener can imagine the content of the narrative – remains obscure and distant; a language that can mostly be appreciated for its unearthly sound.

This yet unreleased work was ultimately performed as a restitution of the Casamia residency at the Bar Pakai, where the trio used to meet and perform originally. Later on, it was publicly executed as a lecture performance by Babau at CRiSAP, London, as part of a six-month period of CHASE AHRC visiting research (Jun-Dec 2025).

In part, we feel that beyond the scope of representation, the work aimed at working as a sonic device to activate the opaque presence of the Fischiosauro and its echoes again among the community. Let’s consider Velia’s thoughts upon listening to the artwork:

Every time we listen to a story, we search our memories for anything that can help us give shape to the characters, places and events that characterise it. This also happens to those who listen to “Elegie pal Fischiosauro.” Our imagination tries to give shape to the origin of the “whistles”, to what happens every evening at dusk in the marshes.

Yet, everything is upside down: the evocative power of words, which, with the right intonation and effective pauses, creates expectation and curiosity in the listener to find out how the story unfolds, has been completely replaced by music and sound. A particular kind of music, made up of sounds that have created the mysterious atmosphere of the swamp and its inhabitant, who moves among puffs, rustles, murmurs and gurgles, occasionally making himself heard but often remaining hidden.

Velia Plotzner, Narrating voice of “Elegie pal Fischiosauro”

As it is clear from Velia’s words, the composition managed to keep the ambiguities of something that is there, but that moves hidden, revealing itself only partially amidst a variety of “animal” sounds. While our work certainly tried to document such happenings through sound art, it also stimulated the ears and memories of Paluzza’s dwellers. Working as an aesthetic and narrative sensory prosthesis for the story, “Elegie pal Fischiosauro” plunges into everything we still have to discover about our relationships with sound and what we stubbornly call nature.

Listen to Elegie Pal Fischiosauro [5]

Acknowledgements:

Babau would like to thank Velia Plozner, Denis Blarasin, Granducato Casali Sega, Mrs Lucia, Casamia Residenze, Le Serre Udine, Marta Oliva, Bar Pakai, CRiSAP, Angus Carlyle, Mark Peter Wright and all the real, hidden and imaginary creatures.

[1] Trumpeter Jon Hassell coined the (now problematic) term Fourth World Music to describe the aesthetic of combining traditional, largely non-European musical styles with electronic sounds and Western avant-garde. The goal is to develop a culturally hybrid sound language that crosses geographical and stylistic borders. The phrase first appeared in the early 1980s, within the context of postcolonial philosophy.

[2] For more context and information, see https://shapeplatform.eu/artist/babau/

[3] See https://www.cafeoto.co.uk/events/discrepant-presents-lagoss-babau-serpente/

[4] Personal communication, Cormons, April 2025.

[5] Audio courtesy of Babau. Streaming availability might change due to developments in the artwork’s eventual discographic copyright.

Bibliography:

Brittan, Francesca. 2011. On Microscopic Hearing: Fairy Magic, Natural Science, and the Scherzo Fantastique. Journal of the American Musicological Society 64, (3), pp. 527–600.

Bubandt, Niels. 2021. The Uncanny Valleys Of The Anthropocene. In Anthropocene Uncanny: Nonsecular Approaches to Environmental Change.

Cohen, Jeffrey J. 1996. Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Feld, Steven. 2025. Acoustemology: Four Lectures. Santa Fe: VoxLox.

Kane, Brian. 2014. Sound Unseen. Acousmatic Sound in Theory and Practice. New York: Oxford Academic.

Screm, Alessio. 2023. Pakai Il Trio Che Si È Fatto in Quattro. Udine: Nota.

Scuola Elementare A Tempo Pieno Di Timau-Cleulis (curated by). 1999. Realtà e Fantasia: nasce la leggenda. Paluzza: Tipografia C. Cortolezzis.

Wright, Mark Peter. 2022. Listening after Nature: Field Recording, Ecology, Critical Practice. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

LUIGI MONTEANNI is a PhD candidate in music studies at SOAS and a winner of an AHRC CHASE scholarship, studying the relationships between contemporary transnational pop music genres and regional music. Currently, he is theorizing the indigenization of extreme metal in Bandung, Indonesia and completing a project of visiting research at CRiSAP London, where he is developing experimental audio devices to test and produce new sonic models and listening protocols.