On the final day of the RMA Research Students’ Conference in January 2016 at the University of Bangor, there was an informative and thought-provoking roundtable discussion on the subject of current issues in HE music. The members of the panel were Dr Chris Collins (Head of School and Director of University Music at Bangor University), Dr Laura Hamer (Associate Professor and Head of Department at Liverpool Hope University), Dr Helen Julia Minors (Associate Professor and Head of Department of Music and Creative Music Technologies at Kingston University) and Professor Rachel Cowgill (Head of Music and Drama at the University of Huddersfield). The presenter for this session was Zaina Shihabi (PhD student at Liverpool Hope University).

We recorded and transcribed the session, and will be posting the contributions from each panel member over the next few weeks. In this first part, Dr Chris Collins reflects on the problems of student recruitment in HE.

Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V

Presenter [Zaina Shihabi]:

Hi everybody, my name is Zaina Shihabi, I’ll be your chair for this session. I’m a PhD student from Liverpool Hope University and I’m the student representative from NAMHE [National Association of Music in Higher Education]. NAMHE promotes the creative, cultural and economic benefits of studying for a music degree by advocating the musical research scholarship and practice at the highest level to ensure healthy and vibrant future for our discipline. We also hold annual conferences that explore themes of relevance to teaching music, community, providing members with the opportunity to develop new ideas, exchange good practice and interact with colleagues from institutions across the UK.

So our first speaker on the panel will actually be Dr Chris Collins. Dr Collins is the head of the School of Music at Bangor University; he is also the vice-chair of NAMHE and a fellow of the Higher Education Academy. While acting as head of school, Dr Collins has forgone the opportunity to reduce his teaching load, in fact he has increased it as he thinks it is really important for the head of school to be seen on ground, especially in the current environment where, as he puts it, teaching is our lifeline. Also, he enjoys teaching immensely. If anyone wants to know, he does keep up with his research. He will go back to it with more vigour when his stint as head of school is over.

First Speaker [Dr Chris Collins]:

Thank you, Zaina. I’m going be talking about student recruitment and I’m going to begin by what sounds like a no-brainer: student recruitment is what academic music is entirely dependent on. And I say entirely because, although there are other sources of income, we could not exist without students. And I don’t think this is widely understood really. We’re no longer in a situation where higher education institutions can just rely on applicants queuing up for places and then we cherry-pick the best ones. We’re getting perilously close to a situation where there aren’t enough A-Level Music students for the number of HE places available. We’re not there yet but we’re heading in that direction and we need to do something about it. NAMHE is very much involved with that at the moment.

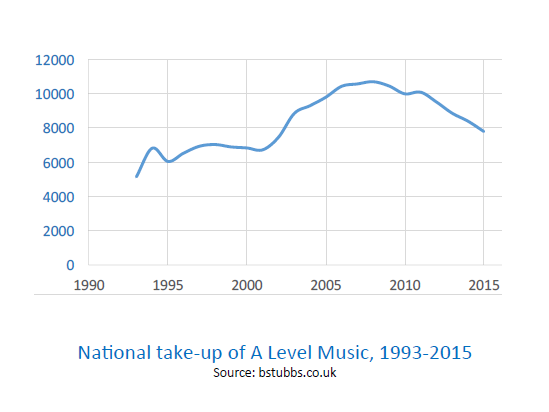

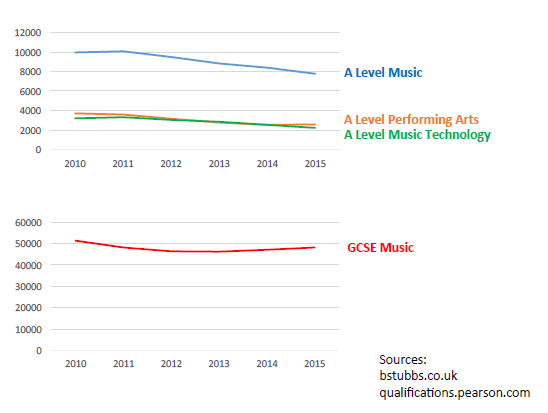

So I’m going to begin with a very sobering thought. The audited accounts of your institution will be available on your university websites somewhere, you will never have bothered looking at them I’m sure! If you do look at them, you’ll find that the income of your institution comes from several sources but the main places will be research grants, grants from government, commercial activities increasingly (hiring out of halls etc…) and tuition fees. Who would like to hazard a guess what percentage of income of this university is tuition fees? (Audience: 30) C: Upwards! (Audience: 70) C: You’re close. Well over 50% of the income of this institution is tuition fees, so you can see how vital it is that we continue to recruit students. Next question: how many of you here did an undergraduate degree at British university or conservatoire? (The majority of hands are raised). The vast majority of you! How many of you did A-level Music before doing that? (The majority of hands are raised). Okay, again, that is the vast majority; that was the traditional route in. In his keynote yesterday, Keith Howard highlighted the recent drop in the number of students taking A-level Music. Now, I’ll put up a graph of the situation since 1993, when the easily-available data begins (see Slide 1 below). The high point was 2008, a period of expansion in most universities, where over 10,000 students took music A-level. Last year’s figure is 7,776. The second biggest drop in all A-level subjects behind General Studies. So what explains the drop in 2,500 between 2010 and 2015? ‘Oh, they’re probably all doing Music Technology instead or Performing Arts’. I’m afraid that’s not so! There’s been a slump there as well and the numbers taking those subjects are very low in comparison to A-level Music. But it’s not all bad news: if I put up the statistics for GCSE Music, we can see that they remain steady (see Slide 2 below). In fact, in the last two years, we’ve seen a slight increase in the numbers of students taking GCSE Music. So the problem is not convincing youngsters that music is something they want to do. The problem happens somewhere around the age of 16: the drop off from GCSE to A-level.

Slide 1

Slide 2

Another sobering thought: if we count every A-level sat in the UK last year, what percentage was in music? Any ideas? (Audience: 4%) Good guess, but actually it was 0.9% (less than 1%). Now if you extrapolate that, thinking that most students take 3 A-levels, and if we think of an average school sixth form with about 100 students in Year 13 (because 100 is an easy number to work with when talking about percentages), that means about 2.5 to 3 students in each school are taking music at A-level. And we all know that schools are not going to run an A-level with that very small number of people, so there is a very real difficulty here where schools are increasingly dropping A-level as one of the options available. I’ll give you one instance from my local area: the island of Anglesey just across the bridge from here has a circumference of 100 miles, it has five secondary schools, how many offer music A-level? One!

So, we need to think about why that is, why that gap is happening between GCSE and A-level. I’m going to show you a couple of reasons why that is. I think one of the most important effects has been the concept of facilitating subjects. These were first foisted upon the world by the Russell Group with good intentions. The idea was to produce some advice for students who didn’t know yet what they wanted to study at university, to help them choose A-levels that would keep the most doors open to them. And this is the list of facilitating subjects [slide change: Maths and Further Maths, English Literature, Physics, Biology, Chemistry, Geography, History and Languages (Classical and Modern)]. So, to be fair to the Russell Group, it was only intended for those students who hadn’t yet decided what they wanted to do. The latest version of the document is full of boxed statements like this (shown on slide), just to make the point that the advice doesn’t apply if you already know what it is that you want to study.

NAMHE has been fighting against the whole idea of facilitating subjects because they are open to misinterpretation. And no-one has misinterpreted it more than the Westminster government, who, in 2012, started using these subjects as the basis for a new league table measure for schools in England (see: Secondary league tables 2012: AAB scores in key subjects). In fact, in 2012, the column showed the number of students in each school who had achieved AAB in three facilitating subjects. What a nonsense statistic! They’ve changed it now, but it still shows two facilitating subjects (the number of students getting AAB in two facilitating subjects plus another one). Now the situation that I’ve described is self-perpetuating, of course. The fewer students that opt to do music, the fewer schools and colleges offer it, and the fewer schools offer it, the fewer students opt to take it.

And what can we do about it as a sector? There are two options, well three, if we include lying down and accepting it. The two other options are: 1) to adapt and 2) to fight, and I think institutions are doing both of those things. One of the ways in which many HE institutions have already adapted is to no longer make A-level music a requirement for study. [Slide change] These are the entry requirements for one randomly-chosen English university – I’m not going to say which one – and if we look at what they are asking for there: A or B in Music, fair enough – we’d all expect to see that, that has been the same for decades – or A or B in Music Technology … plus Grade 5 theory. If no A-level in Music or Music Technology, either AAB or ABB plus Grade 8 performance and Grade 5 theory. So this is a very prestigious Russell Group English university that is sensibly offering that arrangement now. Another adaptation, of course, is to increase recruitment of international students, who also happily bring large fees with them too. A third is to offer new courses that appeal to a particular niche that may not have been covered by traditional music degrees. A fourth adaptation, not one taken by university music departments but by university executives, is to reduce or to size-down music departments to match the number of students coming in, or even to close them altogether.

Or we can fight: that was the second option, of course. One way in which several institutions are doing this already is to refocus the energies that we used to do going out into schools and presenting to A-level students, into doing that for GCSE students in the hope that that will make them want to take A-level and therefore, perhaps, just make music safe in that school for another year at least.

Obviously, it’s best that music remains a school-based subject. Taking in students with ABRSM qualifications is a great thing to do – they are very good students often – but it’s a stop-gap. It doesn’t address the social inequality resulting from the fact that the only students who have ABRSM qualifications are those who have been financially able to take private tuition for many years before reaching that point. So NAMHE has recently been working very closely with ISM [Incorporated Society of Musicians] and MEC [Music Education Council] to make sure that A-levels in Music and Music Technology remain attractive options to 16-year-olds. And to that end, we’ve been involved in public consultations and high-level meetings with the Department of Education; committee members have acted as advisors to AQA, Edexcel and WJEC.

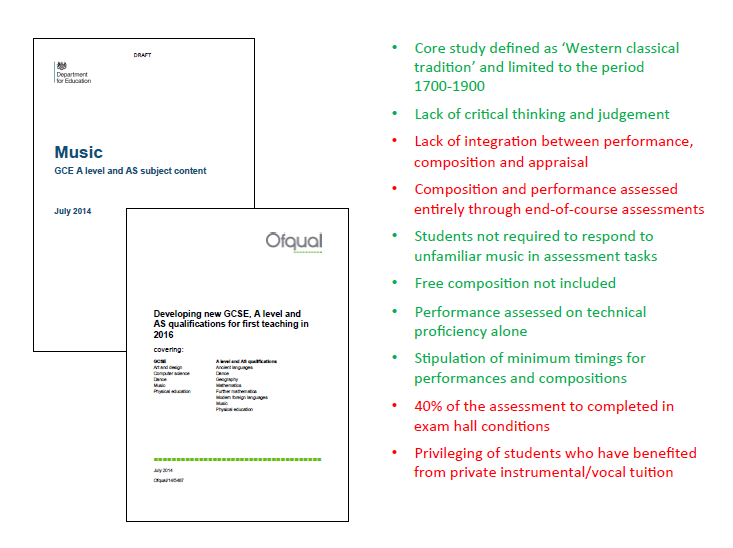

I just want to look at our work on A-level Music as a case study of what we are doing. This is the consultation document that the government put out 18 months ago (see Slide 3 below). We really mustn’t give up on A-level music, though I have to confess that many of us were tempted to do exactly that when the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition came in and decided to make A-levels ‘more academic’. Keith Howard yesterday in his keynote said that he felt that this was driven by universities, but I can assure you that that is not the case. The experience that I have had in this process is that universities very much want to make these qualifications attractive. My own experience suggests that the increased academic leanings are being led from the independent school sector.

Slide 3

These were some of the problems that we identified with the proposed A-level, and we discussed these both person-to-person and presented documents for the DfE and Ofqual as well. I’m just going to colour code what our successes and what our failures were. Green equals success and red equals failure. It’s about a half-way success rate, but we did have an effect on this. The original idea that Western classical music should be the only thing that everybody has to study has now been changed so that they have to study one area outside Western classical music too. And the period of 1700 to 1900 has been expanded hugely to 1650 to 1910. [Audible laughter] Students are now required to actually write in their exam about a piece of music they haven’t heard before, so they’re using critical skills of judgement and not just learning information that they reproduce. Free composition is a key element which it wasn’t before, they only had to compose to a brief. Performance assessment now refers to things like stylistic considerations as well as just playing all the right notes in all the right places. And there was this crazy stipulation that a composition submitted for A-level had to be at least three minutes long, a performance had to be at least three minutes. So the Chopin Minute Waltz was out, but if you played Debussy’s Footsteps in the Snow, that was fine because it was slow and lasted for three minutes. I should say actually that I need to turn that one red because having agreed that they would do that, Ofqual then went back on it and put it back in to some extent at the end.

What we didn’t succeed with are the two points at the bottom of the slide here. 40% of all the assessment is completed in exam-hall situations – which literally means hundreds of people sitting in a sports hall, behind a desk, writing. Big change – we wanted to develop process and communication as the means by which A-level music would be assessed. And then there’s the point I’ve already made about the privileging of students from financially better-off backgrounds. We’re now making similar representations with regard to the new Music Technology A-level, which was even worse in its original guise than this, in that it had no creative element in it at all – it was essentially going to be a qualification for sound engineers, and we have been working very much on making the point that it needs to be creative to reflect how the real world of music technology works, where everybody goes in and contributes in many different ways. And we’re about to do the same thing with B-tech as well.

So, I hope I’ve demonstrated how as HE professionals we can’t afford to take our eye off the ball, and we can’t any more continue to expect the applicants to knock at our door. We have to do our bit to convince them that they want to do a music degree, and even though most institutions are now accepting students without A level music, we can’t actually allow music to drop out of the school curriculum and just go into the periphery somewhere.

Another piece of work that NAMHE has been doing is to produce short videos encouraging young people to take music as a degree subject. If we have time at the end, I’ll play you one of those videos [see: The Value of a Music Degree]. Thank you.

[Applause]

My son wants to study A level music at his school but since there are currently only 3 internal students committed to it they are dropping the A level for this forthcoming school year.

Is there anything I can do to reverse this decision?

Dear Simon,

This is an excellent question and one the RMA Student Blog cannot answer. Please feel free to email NAMHE members (http://www.namhe.ac.uk/about/committee.htm) for further advice on this matter.

Best wishes,

RMA Blog Admin