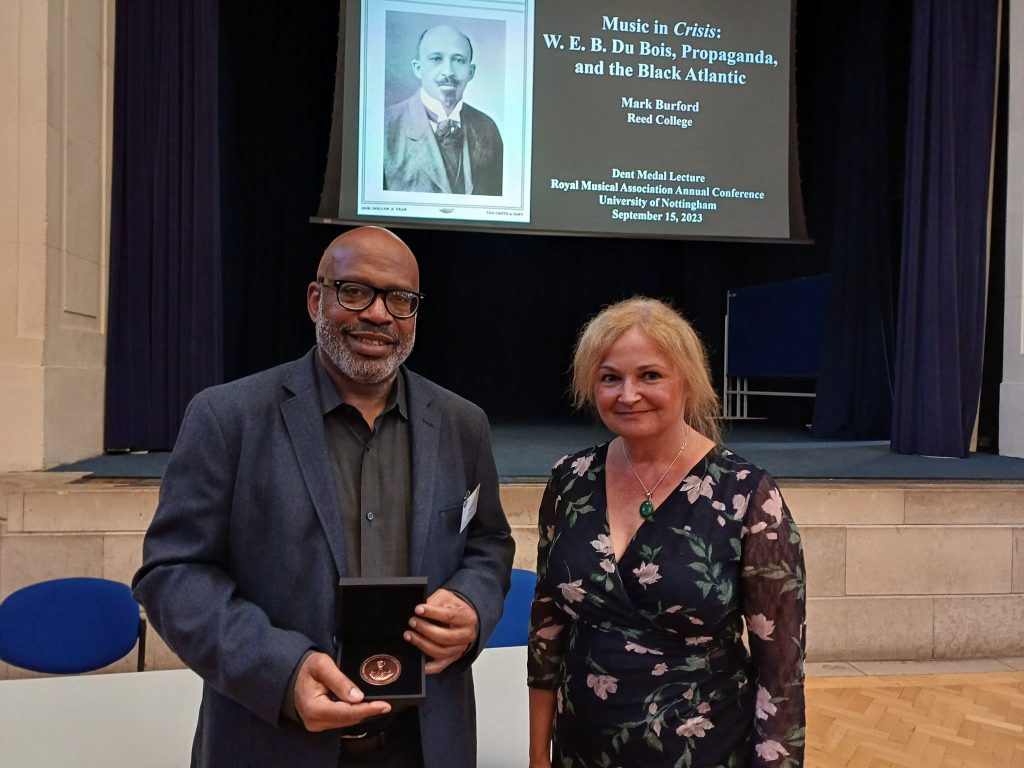

Following the keynote lecture by the 2022 Dent Medallist at the 59th Royal Musical Association Annual Conference held at the University of Nottingham, medal recipient Mark Burford was interviewed by RMA Student Committee member Nicholas Ong who prompted discussions on W. E. B. Du Bois, academic pathways, and his alternative career. Below is an edited transcript of the interview which was conducted on 16 September 2023.

Mark Burford is R. P. Wollenberg Professor of Music at Reed College. A music historian, his scholarship and teaching focus on twentieth-century African American music and long-nineteenth-century European concert music. His published writings for both academic and general audiences include articles on Johannes Brahms, Alvin Ailey, gospel music, and opera, and his article ‘Sam Cooke as Pop Album Artist – A Reinvention in Three Songs’ received the Society for American Music’s 2012 Irving Lowens Award for the outstanding article on American music. He is the editor of The Mahalia Jackson Reader and author of Mahalia Jackson and the Black Gospel Field, which in 2019 received the American Musicological Society’s Otto Kinkeldey Award for the outstanding book in musicology by a senior scholar.

Nicholas Ong (NO): Would you be able to provide a summary of your Dent Lecture?

Mark Burford (MB): The lecture was in three parts. The first was an introduction to my current work on W. E. B. Du Bois and music. It is narrowed to Du Bois and The Crisis which was the main organ of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) co-founded by Du Bois. He was the NAACP’s head of publicity and publications and founding editor of the magazine and I highlighted how music was considered in the magazine. There was a lot of music coverage.

And then I backtracked into how Du Bois got into doing that which included his thinking about propaganda as the mode of persuasion that he wanted his work to accomplish. He wrote about politics and produced data about Black people, Black musicians, and Black cultural figures as pro-Black propaganda against all the anti-Black propaganda. We tend to think negatively of propaganda because of some form of inherent misinformation, but for Du Bois propaganda can also correct this misinformation.

The final part considers the interaction between Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Du Bois. They met several times and Coleridge-Taylor’s obituary was included by Du Bois in The Crisis. Coleridge-Taylor read Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folks and wrote a piece titled Six Sorrow Songs inspired by the book. So, I think of Coleridge-Taylor in this transatlantic context, his connection with Du Bois and how Du Bois saw Coleridge-Taylor as positive propaganda for Black people.

NO: I’m going to pick up on the propaganda idea, though I should say I’m no expert on German philosophy. The poles of propaganda and anti-propaganda sounds to me like Hegelian dialectics. Granted that the propagandas don’t arrive at some form of ‘synthesis’ in Hegelian terms, but do you think he might’ve been influenced by that, especially given his period of study in Germany?

MB: That’s a very interesting observation. Yes, he did indeed spend some time in Berlin in the 1890s and studied with teachers who guided him through Hegelian philosophy. I think he was very interested with the Prussian school of historiography and how they were constructing a narrative of Prussia’s history that had been a source of nation-building for the unification of Germany. Du Bois was, oddly enough, an admirer of Otto von Bismarck because he saw the German question of how to make a people out of these dispersed people as an analogue for Black people. ‘How do we think about these displaced free slaves and the afro-diasporic community as a people?’ was Du Bois’s question. He admired how Prussian historians, such as Heinrich von Sybel and Heinrich von Treitschke, were in the archives collecting data to produce a narrative that help congeal a people. Du Bois saw The Crisis as the platform to generate data and tell a story that up till then could not be told because of a lack of data. I see it as less a philosophical and more a historiographical endeavour that he undertook.

NO: There seems to be a similarity here with Johannes Brahms’s admiration of Sybel and this type of historical work, which you have also written about. Were you struck by the similarity when working on Du Bois?

MB: I was doing my research on Brahms in Vienna and became fascinated with Prussian history because Brahms was a Prussian nationalist, even though he was German. He had copies of books by Sybel and Treitschke and that was how I discovered them. It was fascinating to discover eventually that Du Bois was also an admirer of Treitschke. I didn’t think that there would be a connection between Brahms and Du Bois, but they meet in this intellectual tradition around Prussian nationalism in the late nineteenth century. Having worked on Brahms, I was able to look at the writings of Sybel and Treitschke with fresh eyes for my work on Du Bois.

NO: So, it was sort of a coincidence?

MB: Yes it was! It is interesting though that the German reunification happened in 1873, which is precisely the same time as the reconstruction in the United States. I have not thought about that before. German nation-building and African-American emancipation seemed to have flowed together.

The Fisk Jubilee singers, on which my students are currently writing papers, who toured Germany in the 1870s, or even the 1880s, were embraced by the Germans who had imperial aspirations as potential missionaries. The singers were seen as delegates to Africa who demonstrated what civilisation can do for Black people. So, that connection between Germany and Black Americans is really interesting. WWI changed Du Bois’s mind about the Germans. He was a Germanophile up till that point. That late nineteenth-century moment is an interesting one. The Germans did not identify with Black people, but they certainly saw themselves as abolitionists. When Du Bois went to Germany to study, he fell in love with Wagner and Beethoven, and went to the opera all the time.

NO: Du Bois also attended Fisk University. Did he have any affiliation with the Fisk Jubilee Singers?

MB: Not with the Fisk Jubilee Singers. But he edited the newspaper at Fisk and wrote a lot about music. That was one of the things that got me interested in Du Bois. I wanted to know about all the ways he engaged with music. He received undergraduate degrees from Fisk and Harvard, and a PhD from Harvard as well. So, he always identified with Fisk. Even in his famous essay ‘The Talented Tenth’, he holds up Fisk as an example of higher education.

NO: So, he does see that as part of his identity, especially considering Fisk as a historically Black college…

MB: Yes, absolutely. Fisk was an exemplar of another form of education alternative to the Booker T. Washington model which was rooted in industrial education. He saw Fisk as a school of higher education in the way we think of such institutions today and it played a key role in educating Black leaders.

NO: The impact of the Fisk Jubilee Singers is fascinating. They toured Europe, came to the UK and sang for Queen Victoria…

MB: Yes! She commissioned a painting of them that still hangs in the University today. That was a really important moment. It’s tricky teaching these things to students sometimes. Understandably, they see the issues of White fascination with Blackness with their twenty-first century perspective, but it’s easy to forget that some of the Fisk Jubilee Singers were born in slavery. It’s an incredible honour for them be singing for the Queen of Great Britain having been born as slaves. My students talk about the appropriation and exoticism of their reception, but the singers must have felt good to be recognised in ways that they have not been before. These two contrasting aspects of their reception is really fascinating to me.

For a lot of Black musicians, even with jazz musicians, they go to Europe and escape that sense of White supremacy entrenched in the United States. It’s not as systemic in Europe as it is in the US. There is more openness and perhaps slightly less oppression. African Americans seem to have experienced more freedom when they travelled to Europe in a certain way.

It was probably apparent to the singers what the commonalities of racial ideologies in the different places which they performed were. Du Bois also talks about this. The different ways in which these ideologies are inflected pushes us to have a more complex analysis of how such ideologies operate.

NO: It’s probably harder to perceive such differences in our more connected world. I presume the differences they experienced were starker, especially in the time of nationalism(s)…

MB: Absolutely. I think globalisation retains not just the economic but also the ideological question. When I hear about the RMA talk about Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) – it’s DEI in the US – the discourse is similar to that of the US, so there is definitely some form of streamlining across socio-cultural contexts.

NO: Going back to the beginnings of your academic career which began with Brahms and his fascination with the historical, what sparked your interest in this specific area?

MB: I was a singer and I sang in a chamber choir in high school. We sang one of Brahms’s double choir motet and it was one of the most amazing thing I’ve ever heard. It was an influential moment for me. I decided to major in music and move on to graduate study with Walter Frisch who was an eminent Brahms scholar at Columbia. I wanted to explore Brahms’s choral music, though it clearly didn’t turn out quite like that. My dissertation was still focussed on Brahms though.

I wasn’t thinking consciously in these terms, but I was also always interested in African American music like jazz and gospel. I think it was easier in academia to start out as a Brahms scholar then pivot to gospel music than the other way around. There would be a lot more scepticism in your credibility as a scholar if you went the latter direction. That’s why there are also jazz researchers who started out as medievalists. The pipeline is very much one-way. There is an inertia towards Black vernacular in terms of studying music.

NO: Do you have any speculations as to why the way to an academic career you took is favoured over the opposite way?

MB: Certainly, when I first entered the field, there was a sense that to do concert music, you will require specialised training and less so to do Black and popular music. I wouldn’t say it’s less the case now but there has been a slight change. If you are going to study Black music now, you need to know about Black history and fulfil other requirements in order to be able to talk about the issues in certain kinds of ways. I’m not sure that the first scholars who made the leap from music conventionally requiring specialised training were as well prepared as scholars who specialise in Black music today. I think Black scholars have a sense of responsibility and that if they don’t do it right, it may not be done right.

NO: There’s an allusion to genre there. Is there a sense that a scholar will have to work on figures like Samuel Coleridge-Taylor or Florence Price to be seen as legitimate before working on figures like Sam Cooke or Mahalia Jackson?

MB: No, I don’t think so. I think that literature on Black popular musicians is flourishing. The library of scholarship on Black classical music is growing, for sure, but it’s still limited. It’s like women in music. You keep talking about Hildegard von Bingen, Clara Schumann, and Fanny Hensel because it seems like that is all there is. If you send a student to study women and music, they come back mostly talking about von Bingen, Schumann, and Hensel. It’s much more difficult to break ground on other women musicians. With Florence Price, for example, we know much more about her because we found her music. There’s definitely a broadening of the scope in research on Black classical music.

At the beginning of my lecture, I also touch on the suspicion of Black classical musicians. What they were fundamentally doing, it was seen, was tapping on the respectability and cultural capital of classical music to elevate the race. I think there are more complex stories to be told about African Americans and classical music. One question would be how classical music survived and functioned within Black communities. For a Black composer to have their work performed by an orchestra was a huge honour, but there are figures like Marian Anderson who learnt to sing in the classical manner from being in a Black community, so there’s clearly a supportive network for the music in the community. They will therefore also take ownership of this music too. These networks, support systems, and the significance of the music are definitely areas worth exploring.

One thing that really interested me surrounding Coleridge-Taylor was the politics of Black classical musicians in the UK. Was the discourse of respectability germane to Coleridge-Taylor? Was he a British composer who just happened to be Black? His Blackness was salient, but I wonder if there was the same kind of discursive field around him that surrounded Black American classical musicians. I’d like to learn more about this.

With the Fisk Jubilee Singers again, it certainly wasn’t the case that they had found Europe to be free of racial prejudice. It was a different kind of othering, more covert perhaps.

NO: I appreciated your point about studying Clara Schumann and Fanny Hensel when it comes to women and music. It feels like there is a reiteration of the Teutonic hegemony present in classical music (which is often represented by Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, Haydn, etc.) instituted by our predecessors Eduard Hanslick and Heinrich Schenker, to name a few. Hopefully, the ongoing work on other women musicians will facilitate the dilution of this power.

MB: Indeed. There is wonderful work on Latin American women musicians as well (such as Teresa Carreño). You’re right, there is a gravitational pull towards the German context that’s hard to escape.

NO: Coming back to your research – do your different research interests (on nineteenth-century concert music and on twentieth-century American gospel) share an approach or are your thoughts on them quite distinct from one another?

MB: That’s an interesting question! I would definitely say that my scholarship tends to be very archive-based and that is consistent across my research on different topics. I looked into newspapers for my work on both Brahms and Sam Cooke. I think archives are really important and the one in New Orleans relating to Mahalia Jackson had a transformational effect. My original project on the circulation of gospel voices in popular culture was only going to include a chapter on her, but since finding the archive, I decided to dedicate the entire project to her due to the trove of materials present in the archive. Similarly, with Du Bois, I’m combing through The Crisis for anything on music. I really like getting the data myself in order to tell my version of the story of Black music because I think there are narrative tropes that people use for it. In other words, I like to be able to tell alternative stories of my subjects.

I also like to access ancillary people through a well-known figure in the centre. Sam Cooke was part of the world of the balladeer; you can get access to other people in gospel music through Mahalia Jackson; there are many different interesting voices in The Crisis which Du Bois edited. I enjoy this process of finding others through these central figures.

NO: And sort of establish a network around them…

MB: Yes, exactly! I like seeing people as part of a network. Centring them initially and then decentring them as the work goes on.

NO: There’s a similarity again with research on women and music as a lot of creative women worked in artistic circles rather than, in contrast to male musicians, in isolation – the demythologising of the ‘lone genius’ aside. Such an approach seems to work especially well for figures deemed to be of minority groups in the field.

MB: It has been proven that studies on female musicians will misshape the model used for study on male musicians because of the different ways in which they operated within the field. Studying the collaboration more prevalent in women’s work in music is definitely more productive.

I also definitely identify as a historian and enjoy talking to historians. I love historical and historiographical work and studying the context around music and musical figures. For my PhD, I studied so much German history and historiography that Brahms got swallowed up a little bit. Sometimes you just have to cater to that moment of curiosity around the music, even if it may seem like productive procrastination.

NO: Where will your research take you next?

MB: I will finish with The Crisis and it will hopefully be published in a book. I’m also at the stage in my career where I think more closely about who I’m writing for. I enjoyed writing the book about Mahalia Jackson as it was targeted at a general audience. I’ve been writing a lot of programme notes and I enjoy it because of the quick turnaround, and you can bring scholarly rigour to audiences who will almost definitely read what you have written. So, I would say that I am looking to diversify the kinds of writing I do, after having thought about who I want my audience to be.

NO: And is diversifying one’s audience an advice that you would give to budding music researchers?

MB: Yes. There are requirements you have to fulfil to get into academia but do also give yourself permission to do the things that you want to do. My career was unconventional in that I didn’t turn my PhD dissertation into a book. Instead, my first book was a different project.

I would also encourage all to not think of graduate school as a trade school. It does not prepare you strictly for a professorial position. There are many skills that one can acquire from doing research and writing a thesis. If you’re asked to prepare a lecture on Hindemith within a few days, you will know what to do even if you aren’t a Hindemith expert. The skills needed to do that are very valuable. Academia is one place where these skills will be useful, but it needn’t be the only place. So, my advice is also to not think of yourself only as a professional academic.

NO: Now on to some (more) fun questions. What would your alternative career be and why?

MB: Hmm…I really love sports, so a fun career for me would perhaps be a sports commentator. I like watching competitions and the way sporting events have a narrative with its own context. What do specific sporting moments mean to some athletes? One could also explore their careers within cities or the role of franchises in sports. I consume sports like I consume literature so I would love to be able to craft stories for sports. That would be a wide left turn…

NO: It sounds like your love for research would also be well catered for in that career.

MB: Yea! I think I will enjoy the element of storytelling in the role.

NO: And finally, what is on your playlist at the moment?

MB: So much of what I listen to is based on what I’m teaching – I guess it also works the other way round – but I’ve been listening to a lot of 80s and 90s hip hop. My tastes tend to be quite retro, though what I’ve been listening to the most in the past year has been music by Black composers from the 1910s and 1920s (like Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Florence Price, and Amanda Aldridge).

I think it’s an exciting time for Black classical music. People want to and are open to hearing it. The scholarship, publication, and performance of Black classical music seem to be working hand in hand at the moment to get it out there, which is certainly fantastic!